In this short video, Katelyn Donnelly gives her views on education reform in developing countries. She argues that it is important to focus on the demand side when developing accountability systems in the context of education. Adequate demand will put pressure on the accountability system, allowing the collection of regular and reliable data. Once demand is there and the data starts being reported, checks can be introduced to ensure the data is of high quality and is not being manipulated.

Katelyn also gives an insight into her views on the role of the private sector in delivering education in developing countries. The private sector can provide a bench mark against which to compare the public system, but it can also provide choice for parents, which is important in the developing world. If the public system is failing, parents will make choices to provide the best education that they can afford for their children. In many parts of the world the best option is low cost private schools. Private schools can provide an alternative to the public system, while at the same time assisting government schools to improve.

Biography

Katelyn Donnelly has worked with DFID as a consultant on the Pakistan Education Sector Reform Programme. She is also an executive director at Pearson where she leads the Affordable Learning Fund, a venture fund that invests in early-stage companies serving low-cost schools and services to schools and learners in the developing world. Katelyn is also an active advisor on Pearson’s global strategy, research and innovation agenda. She serves as a non-executive director and strategic advisor for several start-up companies across Europe, Asia and Africa. Previously Katelyn was a consultant at McKinsey and Company and graduated from Duke University with high distinction in economics.

Resources

Katelyn was one of the authors of ‘Oceans of innovations’ – a report that discusses the future of education. In the report, it is assumed with near certainty that the Pacific region will take primary leadership of the global economy in the near future. The authors explore the implications for their education systems, calling for a ‘whole-system revolution’ in the structure and priorities of teaching and learning in the region. The education revolution will need to be based not just on what is currently shown to work but also on the innovative capacity of systems, which will require strong leadership.

In an essay, written by the same authors, titled ‘An avalanche is coming: Higher education and the revolution ahead’, it is argued that there is an opportunity for the next 50 years to be a golden age for higher education if all those involved in the system seize the initiative and act ambitiously. If not, an avalanche of change will sweep the system away. Deep, radical and urgent transformation is required in higher education. The biggest risk is that as a result of complacency, caution or anxiety the pace of change is too slow and the nature of change is too incremental. Citizens, university leaders and governments are urged to act boldly and called upon to contribute to change higher education for the better.

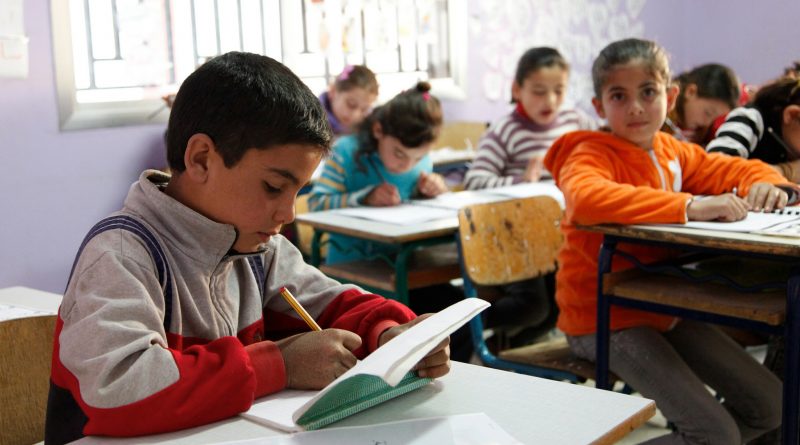

In an Education For All blog written by Katelyn and Michael Fullan it is argued that given the potential for evolving education systems, the stakes for developing countries are high: “To date the international community has emphasized getting every child in schools. Across the developing world indeed enrolments have risen, primary enrolment up to 90% in 2010 from 82% in 1999. Unfortunately the enrolment improvement has not been matched by an increase in achievement. The next round of millennium development goals will likely include a measure of education systems to improve student achievement scores. If systems can unlock the full promise of digital innovations the results will be transformation in outcomes. If not, education achievement trajectories may remain unaltered and we risk losing a generation.”

A recent HEART Helpdesk report focused on the time taken for inputs into education or policy reform to affect learning outcomes. This synthesis of the evidence found that it is difficult to assess the time it takes for inputs or reforms to affect learning outcomes. Attributing changes in results to system-wide reforms can be complex when there are many different programmes and elements affecting outcomes. Data are not always available on learning outcomes over time and may be complicated by changes in testing. Learning outcomes also vary between regions within countries.

Katelyn can be followed on twitter: @krdonnelly

This HEART Talks video is part of a series of resources on education reform in developing countries. The accompanying HEART Talks videos are: